If you love Japan and reading you’ll enjoy my books. They’re available from Amazon and most online retailers.

Kyoto Journal’s “Cultural Fluidity” Issue and My Review of Honeybees and Distant Thunder

Kyoto Journal’s latest issue, “Cultural Fluidity”, is now available to download.

Overflowing with captivating content, Magda Rittenhouse‘s poignant piece on Ryuichi Sakamoto, the “godfather of electronic music”, brought tears to my eyes. Li Zizi’s Chinese flower paintings are breathtaking. There are also compelling features on jazz, punk music, and the rich history of Noh and the new “Noh”. This issue is a delight to explore. You’ll enjoy reading articles exploring Japanese emoji meanings, profound reflections on Nikkei community experiences, and haiku, as well as fantastic reviews courtesy of Patrick McCoy, Leanne Ogasawara, Kala Ramesh, David Cozy, and other esteemed writers. Trust me, this issue is a must-read gem.

My review of ‘Honeybees and Distant Thunder’ by Riku Onda is on page 114. Here’s a snippet of that review:

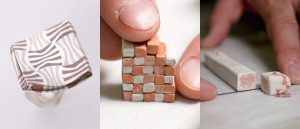

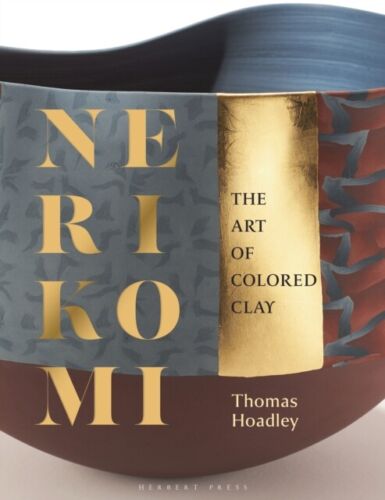

Review of “Nerikomi: The Art of Colored Clay” by Thomas Hoadley

Thomas Hoadley, born in North Adams, Massachusetts, and raised in New Hampshire, graduated from Amherst College in 1971 with a BA in studio arts. After a brief foray into architecture and extensive European travel, he settled in southern Vermont with his wife, apprenticing with potter Malcolm Wright in the karatsu style of wood-fired pottery. Hoadley later earned a Master of Science in Ceramics at Illinois State University, establishing his pottery studio in the Berkshires.

His coloured porcelain art pottery, created using the Japanese nerikomi technique, is featured in public museum collections such as the Museum of Fine Arts – Boston, the Museum of Fine Arts Philadelphia, and the White House Craft Collection (now at the Clinton Library).

In his book Nerikomi: The Art of Colored Clay published by Herbert Press, Hoadley includes examples of nerikomi as well as neriage. The Japanese word “age” means “to pull up” so neriage means to pull up the mass of mixed clay that is thrown onto the wheel. Neriage refers to wheel-thrown coloured clay pottery while nerikomi refers to hand-built, often press-moulded coloured clay pottery.

Large arabesque, 2018. Height: 8 inches, width: 14 1/2 inches, depth: 8 1/4 inches (20.32 x 36.83 x 20. 96 cm) © Thomas Hoadley. Page 60.

In the image above from page 60, one can readily appreciate that Hoadley’s ceramics stand as a testament to true artistic brilliance.

Hoadley provides a fascinating and informative introduction in his book on nerikomi, explaining how the Tang Dynasty in China and the Goryeo Dynasty in Korea witnessed significant artistic achievements with marbled ware produced using two and three colours of clay, respectively. In China, the marbled ware combined white and reddish-brown clay, while in Korea, three clay colours were fired at high temperatures (p. 13). During the Song Dynasty in China (960-1279), white, brown, or black stoneware and porcelain were crafted.

The practice of using colored clay persists in regions with naturally occurring multicoloured clay. Tokoname in Japan, the oldest of the Six Ancient Kilns, exemplifies this tradition, with kilns producing various items such as teapots, bottles, and tiles as early as the Heian Period (794-1185). At its peak, Tokoname housed over 30,000 kilns (p. 23).

Hoadley explains how nerikomi, first observed in the early 1900s, was initially crafted by Kawai Kanjirō (1890-1966). By the early 1950s, Kawai ventured into creating less traditional and more sculptural ceramic shapes.

Hoadley goes on to tell the reader that in the 1970s, Yūsuke Aida (1931-2015) popularized nerikomi in a contemporary manner. Aida introduced nerikomi coffee cups in TV ads for the Nescafé Coffee Company, distributing 100 cups to the first 100 callers and swiftly bringing attention to this unique pottery technique.

JAPANESE MASTERS

The “Japanese Masters” section in Hoadley’s book, starts on page 25 and showcases five Japanese artists who have dedicated their life’s work to the art of nerikomi or neriage, presenting stunning examples of coloured clay art. These Japanese ceramists serve as a profound source of inspiration and guidance for all the featured artists from around the world in this book.

Matsui Kōsei (1927-2003) and Itō Sekisui V (b. 1941) have earned “Living National Treasure” designation for their contributions to Japanese heritage through their exceptional work.

Kōsei’s father was a kimono maker and it seems likely Kōsei was highly influenced by the colours used in the fabrics that form obi, kimono, and obiage. His body of work offers a visually exciting array of techniques and styles. Kōsei’s dedication to the art of coloured clay has served as a direct inspiration for many contributors in this book, challenging artists to experiment and discover new ideas and methods.

An ancestor of Itō Sekisui V relocated to Sado Island near Niigata around 1640. In 1844, the discovery of vibrant red mumyoi clay in a local gold mine became significant. Sekisui utilizes the nerikomi method, blending red mumyoi clay with local yellow firing clay, creating stunning cascades of flower petals and blossoms against a black backdrop. As seen in the image below from page 32.

Square jar with flower patterns, stoneware, 2016. Height: 9 7/8 inches, width: 5 1/2 inches, depth: 5 1/2 inches (25 x 13 x 13) Image: © Itō Sekisui V. Page 32.

Ogata Kamio (1949 – 2022) specializes in wheel-thrown neriage, combining neriage and nerikomi techniques. He intricately layers paper-thin sheets of coloured clays, producing subtle colour graduations. He likes to work with greys, teal, and off-whites. Kamio’s artistic pursuit focuses on infusing “motion” into nerikomi designs, aiming to convey more than delicacy and refinement. His work seeks to bring heightened emotion and feeling to the art of nerikomi (p.35).

Kondō Takahiro (b. 1958), born into a renowned ceramics family in Kyoto, employs coloured clay among various other techniques for crafting traditional ceramic forms and sculptures. Despite initially pursuing a literature degree at Hosei University, he returned to his roots at 26, delving into wheel throwing and glazing. After apprenticing under his father’s expertise in the art of sometsuke, he expanded his exploration into other styles. In 1990, his debut exhibition marked the beginning of international recognition. Over time, he developed the gintekisai glaze, which he dubs “water born of fire.” Embracing water in its various physical forms — rain, ice, steam, and mist — his work embodies the “utsuroi no bigaku” or the art of impermanence. Kondō aims to evoke the beauty found in the ephemeral, illustrating the cycle of nature, purification, and rebirth. An example of his work can be found in the image below from page 43.

Ginteki wan nami (Wave Tea Bowl with Silver Mist Glaze), 2020. Height: 3 3/4 inches, diameter: 4 3/4 inches (9.5 x 12 cm). Rounded tea bowl in black, grey, and white marbleized clay with gintekisai (silver mist) overglaze and hand-brushed cobalt glaze decoration. Marbleized porcelain. Image: Joan B Mirviss Gallery Ltd © Richard Goodbody, Kondō Takahiro Page 43.

Born in Gifu in 1948, Nishi Koichi (b. 1948) is recognized for his mastery of coloured clay, particularly his intricate pattern-making. Renowned for his precision, he adds surface textures that lend a captivating level of mystery to his work (p. 25). Koichi employs subtle colour variations in repeated geometric designs, showcasing remarkable attention to detail. Notably, he achieves a distinctive pebbly texture using a spoon.

COLOURED CLAY WORLDWIDE

In the “Colored Clay Worldwide” section, Hoadley introduces 26 incredibly talented ceramists from all over the world. While it’s impossible to feature all of them in this blog post, let’s explore 12 artists who caught my attention:

Hans Munck Andersen from Denmark uses brightly coloured porcelain, rolling out long coils twisted together for a “candy cane” effect, as seen in the images below featured on page 67 and page 69.

Sea Conch, 1985. Height: 6 1/2 inches, diameter: 8 1/2 inches (16 x 21 cm) © Hans Munck Andersen. HMA Polychrome porcelain bowl. Page 67.

Janny Baek born in South Korea and raised in Queens, New York, creates organic forms in vibrant colours. Baek says, “From my experience working in animation and toys, I bring an interest in the playful, imaginary, and sci-fi, and my experience in architecture has trained me in materiality and design.” (page 70).

Curtis Benzle from the USA, originally explored the colour dynamics of glass, but he transitioned to ceramics. He produces fragile porcelain vessels and embraces the Japanese kintsugi tradition by filling cracks with gold. An image of his work can be found below and at the top of page 75.

Migration, 1986. Height: 8 2/3 inches, width: 17 1/3 inches, diameter: 4 inches (22 x 44 x 10 cm) © Curtis Benzle. Page 75.

For Angela Burkhardt-Guallini from Switzerland, the specific type of porcelain clay is paramount. After winning a Bronze Award in the ceramics competition in Mino, Japan, she discovered a porcelain body from Seto, Japan, known for its pure white colour and beautiful shining surface. Developing an admirable artistry, her work is showcased in the image below and at the top of page 80.

Line to Line #1, 2018. Height: 5 1/2 inches, width: 10 3/5 inches, depth: 10 3/5 inches (13 x 27 x 27 cm) © Angela Burkhardt-Guallini. Page 80.

Ben Davies, a professional cellist hailing from England, has found that working with soft clay provides therapeutic benefits for hands fatigued from extended cello playing. Drawing inspiration from his academic background in Geography and Geology, his ceramic creations reflect the intricate beauty of geology and landscapes.

Barbara Gittings, with a background in fashion and design, built a successful career in the fashion industry spanning both South Africa and the UK. She has now transitioned to a full-time focus on ceramics in London, channeling her creative energy into this expressive medium. She is drawn to “irregular repetition, primitive mark-making, and soft, earthy colours.” (page 103).

Part of Barbara Gitting’s nerikomi process: “I place the slabs into the mold, joining the beveled edges with slip as I go, cutting away the excess. Sometimes I leave space to add a different patterned rim.” (page 107).

Dorothy Feibleman has given lectures, and demonstrations, and taught on an international level. She was born in the United States but she has lived and worked in England and Japan. Feibleman has an interest in combining nerikomi with jewelry. Her innovative work includes a necklace that is on display in the Victoria and Albert Museum collection. Feibleman has also received two tool and process patents for extruders, making almost limitless nerikomi imaging for tiles, tableware, and objects. She currently collaborates with or has designed products for Noritake, Wedgwood, Herend, and Kohler. She also developed a porcelain clay body for Pottery Crafts England. You can see an example of Feibleman’s work in the image below from page 97.

Detail of Desert Lotus, 2006. Total installation size: height: 23 2/3 inches, diameter: 59 inches (60 x 150 cm) Hand construction: laminated graduations of two different porcelains. Image: © Dorothy Feibleman; photo by Ken Yanoviak. Page 97.

Robert Hessler, who studied at the School of Visual Arts in New York, specializes in vertical vase forms and crystalline glaze work. He’s consistently pushing boundaries. Despite a relatively short period working with clay, he has an impressive body of work.

In a brief period, Narumi Ii from Australia who was born in Japan has made a remarkable impact on the ceramics world. Inspired by a chance encounter with a friend in 2016, she enrolled in a pottery class, discovering a natural affinity for clay. Self-taught in the basics of nerikomi, she has elevated the technique by painting intricate multicoloured designs onto ceramic forms, utilizing up to 200 different colours. See the image below of her vase from page 119.

Somewhere in my Dream, 2018. Height: 12 1/2 inches, diameter: 5 3/4 inches (32 x 14.5 cm) © Narumi Ii. Page 119.

After a successful career in design and printing, Judy McKenzie from England made a radical decision at the age of 57 to pursue a passion for three-dimensional Craft and Design at Havering College in London. She went on to obtain her Master’s Degree at the Royal College of Art, where she was introduced to the world of coloured clay. To address the common issue of cracking in nerikomi, McKenzie also embraces the Japanese art of kintsugi, accentuating porcelain tears with gold or silver leaf. Featured below is her work “Pink Cloud” from page 131.

Pink Cloud, 2020. Height: 6 1/3 inches, diameter: 4 3/4 inches (16 x 12 cm). © Judy McKenzie. Page 131.

Anne Mossman joined the ceramics program at the Australian National University in Canberra after a career in management. While studying, she had the opportunity to learn from visiting artist Dorothy Feibleman, sparking her passion for ceramics. Mossman now incorporates paper into her clay to reduce cracking, and her unglazed, high-fired vessels showcase clean cylindrical forms that evoke a natural and bark-like aesthetic. You can see an example of Mossman’s work in the image below and on page 136 of the book.

Seams of Bold, 2021.Height: 11 4/5 inches, width: 6 inches, length: 7 1/2 inches (30 x 15 x 19 cm). © Anne Mossman. Page 137.

In his conclusion, Hoadley explains that while the Japanese terms ‘nerikomi’ and ‘neriage’ may have simple definitions, the artists in this collection showcase the extraordinary diversity these basic concepts can take. Each artist, guided by their inspiration, reimagines and expresses these techniques with distinctive creativity.

Larissa Warren relocated her family and ceramic studio to Tamborine Mountain, nestled in the picturesque Scenic Rim region of Queensland, several years ago. Renowned for its vibrant pottery tradition, particularly among women artisans since the 1940s, this area sparked Warren’s deep curiosity. Undertaking an extensive research endeavor, she delved into the locality’s historical legacy and embarked on a quest to unearth forgotten clay deposits and subsequent techniques.

As an artist, Warren is committed to treading lightly on the land, honouring the ancestral heritage of the Wangerriburra people with reverence and respect. Armed with a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Queensland College of Art and a Bachelor of Arts in Art & History from Griffin University, she brings over two decades of experience as a certified Art and Media educator. Her work can be viewed from page 163 and in the image below.

Black-and-white vases from “Layers of Place” exhibition, 2020. Height: 4 1/2 inches, width: 4 1/2 inches (11 x 11 cm)

I’d like to thank Elle Chilvers, the Senior Marketing Executive at Bloomsbury, for sending me a review copy of this beautiful book.

“Nerikomi: The Art of Colored Clay” by Thomas Hoadley, ISBN-13: 978-1789941692, 160 pages, Herbert Press (18 Jan. 2024), hardcover £30.00.

All images are copyright © 2024 Bloomsbury Publishing, Thomas Hoadley, Herbert Press.

If you’re interested in learning the art of nerikomi in Tokyo, Japan you can take a Nerikomi Certification Course, sponsored by Aida Chemical Industries Co., Ltd.

Happy New Year 2024!

Happy New Year 2024! Thank you for your support in 2023. I appreciate it and look forward to reconnecting with you again this year.