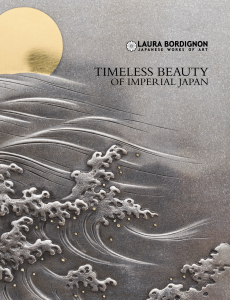

Enter this month’s competition: scroll to the end of this blog post to find out how you could win a highly prized copy of Laura Bordignon’s publication Timeless Beauty of Imperial Japan.

THIS COMPETITION HAS NOW CLOSED. THE WINNER IS HIROMI @OnigiriAction1 ON TWITTER. THANK YOU TO EVERYONE WHO TOOK THE TIME TO ENTER AND LEAVE A COMMENT. EACH TIME YOU ENTER A COMPETITION ON THIS BLOG YOU INCREASE YOUR CHANCE OF WINNING IN THE FUTURE.

Laura Bordignon, based in Berkshire in the UK, is a connoisseur of Japanese works of art. Laura first developed an interest in this subject in 1997; in particular, metalwork and okimono (decorative objects for display) from the Meiji period of which she now has significant knowledge. This talented curator regularly acts as a consultant to international clientele, advising collectors on how to expand or begin their collections. She’s also a specialist on how one should take care of these fine objects created by highly skilled Japanese craftsmen.

Laura was elected as a member of the British Antique Dealers’ Association (BADA) in 2000. She has been a council member since 2007 and she was the Regional Representative for Eastern England for BADA from 2007-2012. These are considered prestigious positions as the vetting process for applicants is based on their high level of expertise.

In 2010, she published an essential reference for collectors, dealers and scholars titled The Golden Age of Japanese Okimono with 200 photos from the Dr A.M. Kanter Collection.

Laura regularly exhibits at events in London such as The Open Art Fair on King’s Road, the BADA Collection on Pimlico Road, and the Winter Art & Antiques Fair at the Olympia Exhibition Centre in London.

Timeless Beauty of Imperial Japan is Laura Bordignon’s latest publication. This catalogue contains over 70 photographs showcasing her finest metalwork, silk art textiles, silver, and Shibayama (inlay of a design into ivory, wood or lacquer) objects. Various legends, myths, beliefs, and folktales are explained alongside the art throughout. They really add to the quality of the text and the appreciation of each piece. This is an invaluable reference for art collectors and connoisseurs. You can purchase a copy of Timeless Beauty of Imperial Japan from Laura’s website.

All of the Japanese artworks featured in this blog post are part of this publication. There’s so much to learn about Japanese culture in this book.

BRONZE VASE BY UNSHO

A bronze vase by Unsho on page 11 (which is strikingly beautiful in its simplicity) is inlaid with koi carp. They cleverly appear to swim beneath the surface. These fish are admired all over the world for their vibrant colours, elaborate patterns, and high price tags. The Japanese believe koi carp are a symbol of a male child as well as good fortune and fertility.

Laura explains how every year on the 5th of May, Japanese families with a son born that year put up coloured carp streamers outside their homes. She goes on to say there are many legends associated with these aquatic beauties. “Dragon’s Gate Waterfall” tells the story of thousands of koi fish swimming upstream in the Yellow river against strong currents and how those that reach the top of the huge waterfall become dragons. A wonderful tale reminding us to continue to persevere when we’re trying to overcome major difficulties in our lives.

GOLDEN PHEASANT BY SHUBI (HIDEYOSHI)

The Japanese bronze figure below of a golden pheasant (Kiji 雉) on page 13 is naturalistically modelled with details worked in shakudo (gold and copper alloy), silver, and gilt, with inlaid glass eyes. It is signed in an oval reserve by Shubi (Hideyoshi) 秀美, Meiji period 1868-1912.

The pheasant in Japan is associated with the sun goddess, Amaterasu, and is a symbol of spring and imperial elegance.

SILVER HAWK BY SHOEIDO

Considered the world’s oldest field sport and often nicknamed “the sport of kings”, falconry has traditionally been favoured by the nobility, aristocrats and royals for centuries. This hobby is the art of rearing, training and flying birds of prey. It’s an expensive sport but fairs, centres, and historic homes have experts on hand who are more than willing to give visitors the opportunity to get close to these birds and fly them. The lucky few who have the good fortune to own a bird of prey will truly appreciate the silver hawk below.

This Japanese hawk perched on a lacquer stand on page 31 is embellished with gold hiramakie (lacquer work) and takamakie (decorative) chrysanthemum flowers, foliage, scrolls and aogai (mother of pearl decoration). The details are in shakudo (gold and copper alloy) and pure gold with a detached silver cup bearing the kikumon chrysanthemum seal. It’s signed in an oval reserve under the tail feathers by Shoeido 松栄堂 and the mark of Jungin 純銀 (pure silver) and also signed under the cup, with a tomobako or wood storage box from the late Meiji period (1868-1912).

Takagari birds (hawks, falcons and eagles) were also popular in Japan with the nobility and samurai class and they were used as a measure of wealth and status. The tradition of falconry in Japan (takagari 鷹狩) is believed to date back to the 4th Century.

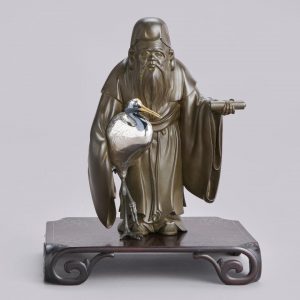

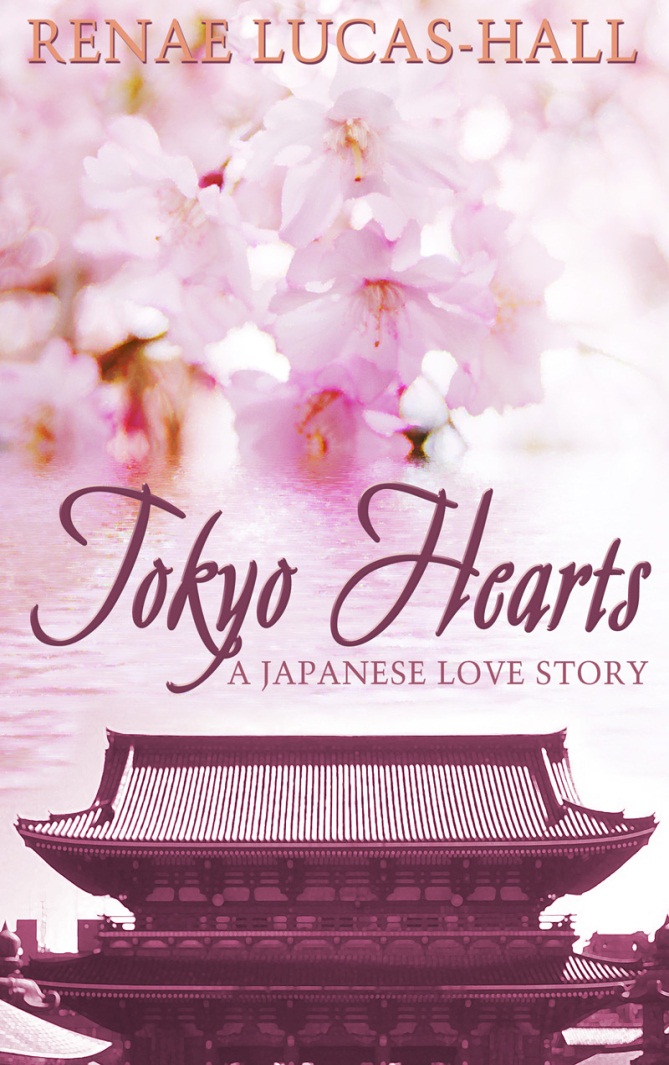

BRONZE FIGURE OF JUROJIN BY SEIUN

This Japanese bronze figure of Jurojin 寿老人on page 41 is the god of learning and longevity. He’s holding in his hand a sacred scroll worked in silver, gold, shakudo (gold and copper alloy) and shibuichi (copper alloy). He’s accompanied by a crane standing on one leg with details finely carved, signed in a rectangular plaque Seiun 晴雲 on a wood base inlaid with fine silver wire decorations, late Meiji period 1868-1912.

Kano Seiun I (art name Kano Ginzaburo) was born in 1871 and studied metalworking under the famous artist Oshima Joun. He exhibited bronze figures of sparrows at the Paris Exposition in 1900 and the 1914 Exhibition in Tokyo. One of his works is in the collection at the Tokyo National Museum.

Jurojin is one of the Seven Gods of Good Fortune known collectively as the Shichifukuju (Seven Happiness beings). This serene god has a snow-white beard and carries a sacred staff of learning with an attached scroll containing the wisdom of the world. He is often in the company of a crane, a white stag, or a turtle, all three emblems of longevity. They are very popular amongst the Japanese as they are considered benevolent friends whose origins derive from Buddhism, Chinese Taoism, and Shintoism.

UNSIGNED EMBROIDERY OF KINKAKU-JI

Anyone who has travelled to Kyoto in Japan will almost certainly have visited the famous Kinkaku-ji 金閣寺 or Temple of the Golden Pavilion.

This Japanese silk embroidery depicting Kinkaku-ji on page 45 is set in a landscape garden overlooking a large pond. It is worked in layers of long and short silk stitches with an original wooden frame, late Meiji period 1868-1912.

Kinkaku-ji is one of the most popular buildings in Japan, designated as a National Special Historic site with two floors covered in gold leaf and set over a large pond that reflects the pavilion.

BRONZE DANCING BOY BY MIYAO

This Japanese bronze dancing boy with a drum wears a festival headdress on page 67. The fine gilt details are worked on grounds of rich brown patination and signed on a rectangular gilt plaque, Miyao 宮尾. The wood lacquered base with foliate scrolls is dated Meiji period 1868-1912.

The Miyao Company founded by Miyao Eisuke had premises in both Tokyo and Yokohama and produced fine bronzes with a rich brown patina and gilded details. The Company exhibited at the National Industrial Exposition (Naikoku Kangyo Hakurankai) in 1881.

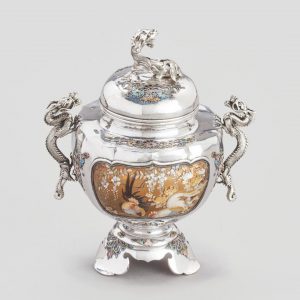

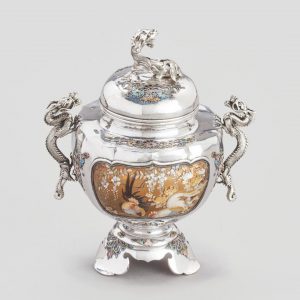

KORO INCENSE BURNER BY SADAMUNE

The Japanese silver shibayama (inlaid lacquer) koro (incense burner) on page 79 is inset with gold lacquer panels finely inlaid in mother-of-pearl, coconut shell, and coral with a design featuring birds and cherry blossoms.

The sides have been applied with writhing dragon handles and the domed cover has a kirin finial, signed in a gold rectangular plaque by Sadamune 貞宗, of the late Meiji period 1868-1912.

The kirin 麒麟 is a mythical creature which is shaped like a deer but looks like a dragon. It originates in Chinese mythology and is known as a qilin. It has cloven hooves and a flowing tail and symbolises goodness and purity.

The cherry blossom design on this incense burner is so pretty. The delicate petals really add to the overall presentation of the koro but there are other spectacular works of art featuring cherry blossoms in this publication which are also incredibly beautiful such as the silver chest of drawers by Shuzan on page 9. The two cloisonné enamel vases: one with a peacock perched on a cherry tree on page 21 and another with sparrows perched on cherry blossom branches in bloom on page 77. And a bronze inlaid vase with a slender neck worked in silver with shakudo cherry blossoms and taro leaves on page 75.

…………………………………………………………………………………….

On page 52, Laura explains to the reader how the fascination with Japanese art started a trend in the West known as Japonisme during the 19th century. The ukiyo-e woodblock prints; in particular, inspired the Art Nouveau movement and influenced impressionist painters like Vincent Van Gogh, Claude Monet and Paul Gauguin. The collection inside this publication of Timeless Beauty of Imperial Japan is so spectacular it’s bound to inspire modern-day art lovers, collectors, or connoisseurs and increase their appreciation of Japanese artworks and the artists from the Meiji period who created each and every masterpiece.

For more information on how to purchase any of the items above or if you’d like to see Laura Bordignon’s collection at an event please visit her website.

WIN A FREE COPY OF TIMELESS BEAUTY OF IMPERIAL JAPAN BY LAURA BORDIGNON. Simply leave a comment below telling us your favourite Japanese work of art in this blog post. The winner will be announced here on the 30th of November 2022.

Please note: This competition has now closed. The winner is Hiromi @OnigiriAction1 on Twitter.