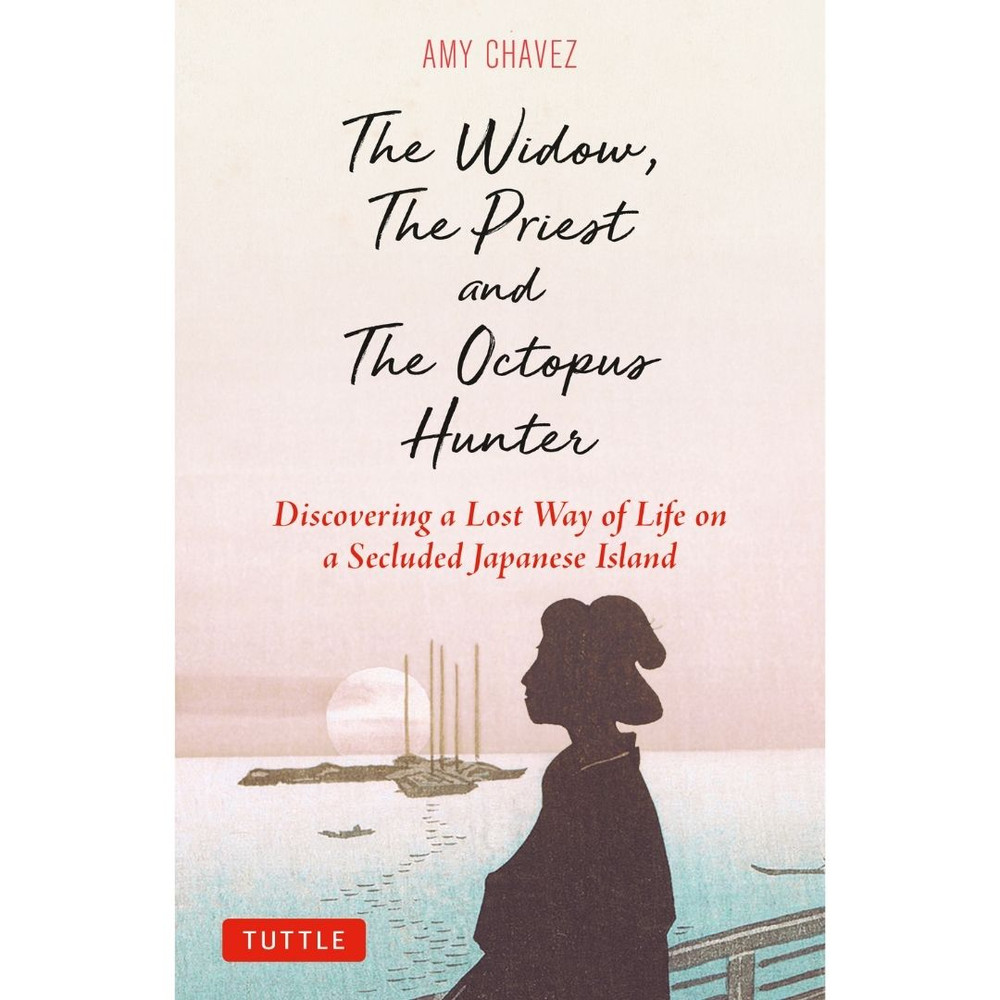

“On this island, I have sat in the eye of a typhoon, seen how octopus are hunted, learned to dance under the moonlight, and wandered like the poet Basho on an ancient pilgrimage trail. I’m still content to watch lavender-colored sunsets from Shiraishi Beach in bare feet rather than a posh restaurant atop a grand building.” — Amy Chavez (“The Widow, The Priest and The Octopus Hunter:” p. 213)

So many books have been written about Japan. Still, very few delve deeply into its cultural core to reveal the secrets the Japanese pass on from one generation to the next. Amy Chavez shares these hidden elements in her latest work of non-fiction. Readers can absorb and appreciate the memories and history of the inhabitants of Shiraishi, an island in the Seto Inland Sea where she has lived for 25 years. This eloquent wordsmith joins the ranks of prominent writers and Japanologists such as Donald Keene and Lafcadio Hearn with the publication of her book The Widow, The Priest and The Octopus Hunter. This is a collection of 31 portraits offering immense cultural value. It’s beautifully written and the interviewees are fascinating, endearing, wise but humble, and intrinsically Japanese.

All seven elements of culture: social organisation, language, customs and traditions, religion, the arts, forms of government, and economic systems are explored within the pages of this book. However, at no point or on any page does it read like a schoolbook or textbook. Although, students would be thrilled to scrutinize the passages on ghosts, a death by fugu puffer fish, and human sacrifices!

Shiraishi Island has just 430 inhabitants with an ageing population. The young have moved to larger islands or mainland cities like Osaka and Tokyo because “iconoclastic children and grandchildren value convenience over tradition” (p. 127). Even the local temple has become more of a hermitage rather than a place for people to gather because of depopulation. The schools are closing because of the lack of children. This is a significant loss because their events brought people together and strengthened community ties. There’s no hospital and the doctor only visits the island twice a week. The elderly who still live on the island are afraid of becoming muenbotoke, an abandoned spirit, with no one to look after their graves (p. 97).

Many Westerners see Japan as the land of Sony TVs, Honda and Toyota automobiles, the birthplace of manga and anime, a country filled with beautiful temples like Kinkaku-ji in Kyoto, and the grand metropolis that is Tokyo with the graceful Mount Fuji acting as a superb backdrop. Not many tourists think of visiting the islands like Shiraishi, a place full of culture with wonderful traditions like the sea ceremony, the insect festival, and the Obon festival when the islanders perform the Shiraishi Bon Dance. But this book by Chavez could facilitate a new way of thinking. Her description of the times she spends with her neighbours during the sakura season is very appealing and after reading such lovely prose others may feel inclined to visit or move to the island:

“Soon, the cherry trees will blossom and we’ll sip sake under their boughs. Someone will bring a guitar and we’ll all sing, and maybe even dance under the trees while perfect pink petals rain down upon us like snowflakes against the backdrop of the cerulean Seto Inland Sea.” (p. 222).

The stories and struggles in this book are interesting because the elderly all grew up experiencing island life. The Doll Maker, Okae, explains how there was no TV or any other form of entertainment when she was an adolescent, so they just talked and socialized for fun. The boys would practise yobai where they’d sneak into girls houses at night to fool around to keep themselves amused (p. 141).

When Tetsumi, a friend of Chavez and a gracious septuagenarian who runs the Otafuku inn, chats about her past she remembers the difficulties she faced with a fond sense of nostalgia. She tells Chavez there was little rice to go around, it wasn’t always grown in Japan, and even though the government distributed it, rice was scarce, and they had to make do with wheat and potatoes. They kept themselves busy just surviving. They had to carry tofu on bamboo poles on their shoulders over narrow mountain paths to the men who worked at the quarries for their lunch. People lived simply on fried food, tofu, and konnyaku. Even senbei rice crackers were sold individually. However, Tetsumi goes on to explain how the 1960s and 70s were more prosperous and people came to the island to stay at the inns and enjoy fresh sushi. The staff wore kimonos and sang enka songs but even then, jobs were scarce on the island and most people were either fishermen or farmers. These memories and the history of Shiraishi Island provide captivating stories for the reader to enjoy. Every account is distinctly unique and they’ll appeal to anyone who wants to explore a different side of Japan.

Chavez’s writing is personal but not purely subjective. She writes mainly of others with hints of her own life. This book proves she gives back to the community and integrates herself into island life wholeheartedly; breaking down the barriers one would expect for an outsider or murahachibu (those not accepted into the community). The photos in the hardback are a lovely and thought-provoking addition. Especially, the picture of Eiko sitting with the other war widows in front of the infamous Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, where it’s believed the souls of Japan’s war dead reside. Her book is definitely worthy of 5-stars and it’s a welcome addition to the world of Japan-related literature written in English.

“The Widow, The Priest and the Octopus Hunter” by Amy Chavez is published by Tuttle Publishing. It’s available to buy on Amazon and from all good booksellers.