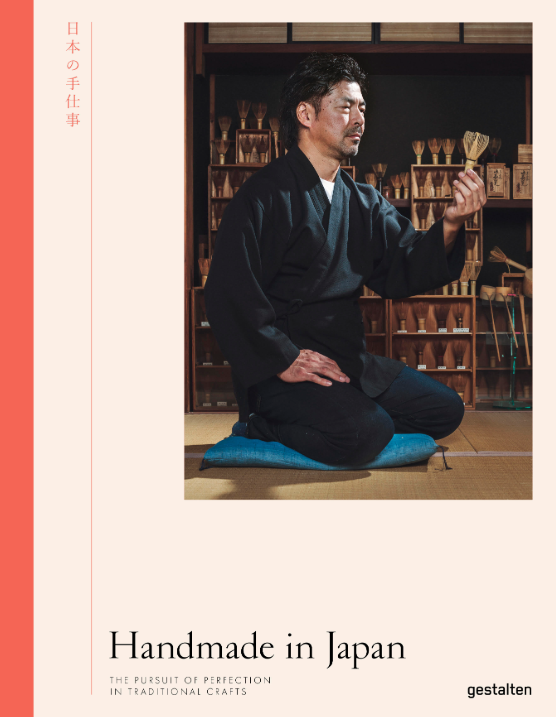

Published by Gestalten

Photos and Essays by Irwin Wong

Famous architect Kengo Kuma provides a thought-provoking introduction but Irwin Wong is the true orchestrator of this beautiful photobook. As you turn each page, it’s Wong’s stunning photos and fascinating essays that introduce you to the exquisite handicrafts and the artisans who make them throughout Japan. The perfectionism and dedication of these people, who are practising skills passed down to them for hundreds of years from one generation to the next, deserves the upmost respect and praise.

Wong goes above and beyond in all of his essays to provide not only a background on each craft, but also meaningful insight into the Japanese culture and its traditions. His explanation on the importance of Noh masks and the way they’re made is one example. Wong explains the masks are made from Japanese cypress for the Noh theatre and each mask is painted differently to depict the character, gender, and age of the player. The expression on the mask also tells us whether they’re human or divine, and even the slant of the eyes can express a different emotion entirely. Wong goes on to explain the Noh actor wearing the mask is able to channel the mask’s character in a way that it becomes an “esoteric ritual”.

There is something in this book for everyone, male or female, young or old. Those interested in samurai swords will enjoy reading about the Seki tradition of sword making, north of Gifu. They have the honour of making swords for the Imperial Family and the current fully fledged artisan is a twenty-sixth-generation master. Equally, the samurai armour restored by Satoshi Tachibana for the Soma Nomaoi Festival is noteworthy. The pictures of the horsemen in full samurai regalia on parade and procession on these pages are magnificent.

Those who enjoy recreational fishing might consider switching from a carbon rod to a bamboo rod after reading about those made in Wakayama Prefecture by Mamoru Yoneda. He says the flex, the response, and the feeling of pulling the fish out of the water is a lot more pleasurable with one of his bamboo rods.

Women with an appreciation of kimono will love reading about the kaga yuzen method of dyeing silk and the fact these kimonos are 100-percent hand-painted (no stencils or printers are used). The work is painstaking but the kimonos can cost up to three million yen. The tea whisks made by Tango Tanimura in Nara Prefecture which are used in sado, or Japanese tea ceremony, look like works of art and are of the highest quality. This family has been making tea whisks for over 500 years. The Kyonui or Kyoto embroidery is so intricate with its Buddhist iconography, this would also be a sight to behold. Wealthy circles and aristocrats from years gone by have always valued this embroidery and prized it as a status symbol.

Wong’s photo of the copper artisans at a 200-year-old company in Niigata is my favourite. For me, it’s an authentic representation of traditional Japanese craftsman. They’re sitting on the tatami mats hammering the copper vessels independently, “smoothing, texturing, curving and compressing” the copper, completely absorbed in concentration. But many readers would say Wong’s portrait photos are his best. The photo on the cover of Tango Tanimura holding one of his tea whisks as well as the pictures of Noh mask craftsman, Kohkun Otsuki, on pages 213 and 214 are fine examples.

It was great to see handicrafts created by the Ainu people in Hokkaido continue to this day. Mamoru Kaizawa is a quarter descended from Ainu blood. He creates Nibutani Ita, large trays for food carved out of wood with intricate Ainu motifs. Another Ainu artisan is Yukiko Kaizawa. She creates Nibutani Attoushi. She harvests tree bark from the Manchurian Elm tree and turns it into a fashionable textile.

Readers who appreciate a trip to a bathhouse in Japan will admire the wooden oke or buckets, created by Shuji Nakagawa in Shiga Prefecture using 700-year-old ki-oke techniques.

Potters will be enthralled by the chapters on pottery and ceramics. The kutani yakimono Japanese pottery is dazzling and the way Reiko Arise is able to hand paint the lines on this beautiful red porcelain with gold accents is remarkable. Koide’s Bizen Yakimono pottery uses a method which is characterized by energetic, muscular lines and a matte finish. It “is counter to the high-tech, highly choreographed image of modern Japan” (pg. 254).

You can see in this book just how much modernization has had a negative impact on traditional crafts. In the 1950s, 600 workshops in Gifu were making 15 million bamboo and washi paper umbrellas per year. Now, only three workshops make 5,000 per year. Japanese people don’t see a need for them. I was pleased to read that foreign visitors are prepared to buy them, even at a cost of USD250 as souvenirs and fashion accessories.

Washi paper makers are also looking at new ways to entice customers. They’re making lampshades, bags, wallets and even earrings because washi paper is so durable. Lanterns made from natural bamboo and washi paper are also being used as furnishings in designer hotel lobbies and boutiques in Japan and around the world.

It’s good to know a school dedicated to learning bamboo crafts in the hot spring town of Oita was established in 1938. The craft flourished thanks to this and it’s still a full-time vocational school. The artisans are now using bamboo to make luxury bags and sculptures for interior spaces as well as traditional musical instruments like the shakuhachi and tea ceremony utensils. This has been pivotal to the continuation of the craft. Early histories of Japan reveal bamboo was considered a magical material. People come from all over the world to learn this craft at the school and there’s a waiting list to get in.

Wong’s essay on the floats for the Nebuta Festival in Aomori is uplifting. This festival which runs for six days of the year is the biggest festival in Japan. It attracts three million visitors every year and this means the creation of the floats is still in full production. It’s ingrained in the hearts and minds of everyone who lives in Aomori because both the young and old as well as carpenters, painters and electricians get involved with the creation and the activities. The hand-painted wood and paper floats, based on folklore or historical battles, can reach up to five metres high. Every year they are made anew.

Readers will be pleased to know the Japanese government has stepped in to preserve certain traditions. We are told that most lacquerware is now made in China or Korea but thanks to an ordinance by the Japanese government that all important Japanese Cultural Property must use the lacquer from Iwate Prefecture, the craftsmen in Iwate have a reason to keep working. But it’s also the hard work of the people of Jojobi in Iwate, the artisans who apply the lacquer, the tappers who cut and extract the sap from the urushi tree, and the volunteer tree planters who are keeping the lacquerware industry going, even though Japanese production only makes up three percent of the market share.

However, readers will be disappointed to learn many handicrafts could easily die out in the not so distant future. One example is the way computers have replaced the abacus, a traditional calculating tool and counting frame. Although there has been some interest from international customers, fifty years from now it might be rare for anyone to hear the hypnotic click of abacus beads made in Shimane.

German publisher Gestalten has produced a beautiful book but the small print under the photos and the pages coloured blue are difficult to read. I also thought it was strange the publisher didn’t add Irwin Wong’s name to the cover or spine of the book.

Overall, this is a lovely photobook. You can tell a lot of time and effort has been taken to deliver such fantastic images and essays. The result is a book so masterfully produced, it provides a deeply personal and captivating celebration of handicrafts and artisans in Japan.

A shorter version of this review has been posted on Amazon.