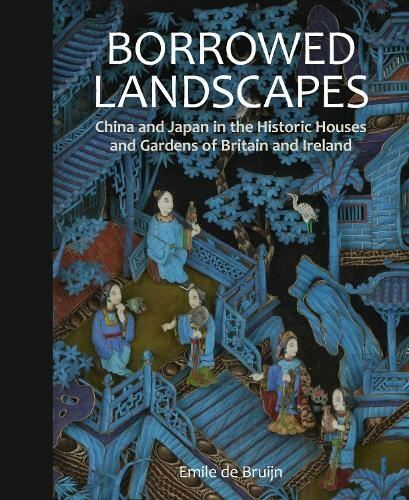

After graduating from Monash University with a major in Japanese language and culture, my enduring fascination with Japan has led me to numerous personal and professional engagements in Tokyo, Melbourne, and the UK. Two decades ago, upon returning to England, a fresh passion emerged — one that involved exploring historic stately homes. This newfound pursuit has taken me across the country, allowing me to appreciate their grand architecture, refined furnishings, captivating artworks, and meticulously manicured gardens. Therefore, it brought me immense pleasure and enthusiasm to read and review the pages of ‘Borrowed Landscapes: China and Japan in the Historic Homes and Gardens of Britain and Ireland‘ by Emile de Bruijn.

This mind-nourishing, exquisitely crafted book delves into the artistic elements borrowed from China and Japan that grace British and Irish houses and gardens, aiming to scrutinize the patterns and mechanisms they unveil. In this blog post, I’ll explore some of the key highlights, bearing in mind the content and stunning images provided here offer only a glimpse of what can be found within the work itself. This extraordinary book, published in association with the National Trust, is a wonderful read and a splendid addition to anyone’s coffee table, be it at home or in an office.

I’d like to express my gratitude to Elle Chilvers, Senior Marketing Executive at Bloomsbury Publishing, as well as Philip Wilson Publishers, and the National Trust for sending me the book and generously permitting me to use the captivating images showcased in this blog post, which are even more splendid within the pages of the book.

A PATTERN EMERGES 1600-1690

Emile de Bruijn, the author, skillfully establishes the narrative tone in the opening pages telling the reader how Marco Polo in the 13th century returned to Italy brimming with enthusiasm; vividly recounting the silk, pearl, and porcelain trade he found in East Asia. Fast forward to around 1600, the Dutch and the British established ‘East India’ trade companies, embarking on a venture to import coveted luxury items. Nevertheless, the cultural significance and integrity of these items were frequently misconstrued and overlooked (p. 10, 11).

De Bruijn goes on to explain how many Asian objects have undergone a redesign to align with European tastes in the past 400 years, with European designers emulating Chinese and Japanese objets d’art. Integrating an Asian stylistic touch, they augmented Asian porcelain and lacquer with precious metals, and reconfigured Asian furniture by dismantling and adding elements, transforming the once ‘exotic’ into something ‘domesticated’ for the European market. Western entrepreneurs, functioning as ‘gatekeepers,’ ordered substantial quantities of specific items from Asia, shaping how Europeans perceived the continent. Renowned cabinet-makers like Thomas Chippendale (1718 – 1779) further refined and marketed their own lines of orientalist furniture (p. 13).

In the 19th century, De Bruijn tells us the Prince Regent (later King George IV) embraced the Chinese ‘style’ to adorn Carlton House, the Royal Pavilion, and the Fishing Temple at Virginia Water. However, a considerable disparity exists between this stylized representation and the authentic culture of Japan and China it seeks to emulate (p. 14). The author notes on page 14 that “Asian objects were copied and adapted with insouciant abandon” during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. Despite the divergence from reality, one can at least appreciate the creative ingenuity of these designers.

In the early seventeenth century, the popularity of blue and white Chinese porcelain, known as Kraak-ware, soared as it was shipped by the East India Companies in England and the Dutch Republic (p. 17) (see image 1. page. 18). The cobalt used to craft the distinctive blue pigment originated from the Middle East and was subsequently exported back to the region, facilitating a global cycle of production and consumption.

1. (Image from page 18, FIG. 1). Porcelain dish with blue and white decoration in the ‘kraak’ style, with auspicious motifs within panels around the rim and an image of birds next to a stream in the centre, probably made in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province, China, late sixteenth or early seventeenth century, diameter 36.8 cm © National Trust/Robert Thrift

Shimmer and sheen played pivotal roles in shaping European appreciation for Japanese lacquer. (p. 20). From around 1580, the Portuguese initiated the flow of lacquer from Japan to Europe. These initial lacquer imports featured inlays of metal foil and mother-of-pearl; a technique honed by the Kōami family of artisans in Miyako (present-day Kyoto) (pg. 20). The tray in image 2. page. 20, crafted in the style of the Kanō school of painting, showcases lions in the centre, symbolising power and protection. The Japanese referred to this style as ‘namban‘ or ‘southern barbarian,’ which was influenced by traders or missionaries from Europe.

2. (Image from page 20, FIG. 3). Lacquer tray in a lobed leaf or flower shape and decorated in namban style with gold and mother-of-pearl on black, the central panel showing a pair of lions under a tree, Japan, c.1600, 32 x 37 cm © National Trust Images/Dara McGrath

The white porcelain figure, depicted in the image on page 25, exemplifies a representation of the Bodhisattva Guanyin. Originating from Dehua in the Fujian province of China, this particular piece dates back to the period between 1640 and 1690. Notably, it gained popularity in the refined interiors of elite British households during the late seventeenth century. Concurrently, there was a surge in the popularity of Indian gowns and Japanese silk kimono within the Dutch Republic (p. 25).

The author points out how the emergence of orientalism in English silver, decorative paper, and tapestries began to unfold during the 1680s and 1690s.

EMBLEMS OF INSPIRATION 1690-1735

De Bruijn explains how during the mid-seventeenth century, the interruption of Chinese production due to the Manchu invasion and the establishment of the Qing dynasty prompted Dutch merchants to redirect their attention to Arita in Kyushu, Japan. Among the Europeans, only Dutch merchants were granted permission to engage in trade with the Japanese. It was during this period, in the late 1670s, that a distinctive type of porcelain named Kakiemon emerged. Characterized by its fine white porcelain and a colourless glaze, Kakiemon was adorned with vibrant red, green, blue, and yellow enamels.

The Chinese lacquer folding screen in image 3. page 72 at Osterley Park in west London is stunning. During this period, China was widely regarded as an advanced civilization, and this particular screen, probably crafted in Guangzhou (Canton) between 1715 and 1720, exemplifies the opulence associated with the time. It was commissioned, in all likelihood, by a member of the Child banking family, potentially Robert Child — an influential figure as a director and chairman of the English East India Company. According to de Bruijn on page 136, members of the Child family had been investors in and directors of the East India Company for three generations. The author tells us this family had added an impressive array of Chinese and Japanese luxury goods to the family’s collections at the time of Robert Child’s death in 1782.

3. (Image from page 72, FIG. 45) Eight-fold lacquer screen decorated in red, gold and silver on black with scenes in and around a mansion or palace, surrounded by pictorial vignettes and representations of the Child family arms, the back with bird-and-flower scenery, probably made in Guangzhou (Canton), China, c.1715–20, 275 x 370 cm © National Trust Images/John Hammond

PEAK CHINOISERIE 1735 – 1760

The word ‘chinoiserie‘ is the term denoting the imitation-Chinese style. During the mid-eighteenth century, Chinese-style garden structures reached the pinnacle of fashion. The era witnessed a widespread emulation of Chinese materials and shapes, and the importation of Chinese luxury products, influenced in part by European taste. Notable examples also include painted enamel, famille rose porcelain, wallpaper, mirror paintings, and miniature pagodas (p. 81).

Two bureaux featuring dressing mirrors at Powis Castle in Wales, one depicted in image 4. page 80, are believed to have been commissioned in England and manufactured in China. However, de Bruijn explains there’s an interesting twist to this hybrid creation because they were sent to Japan for the addition of lacquer. This serves as a noteworthy example of fully hybrid yet prestigious orientalist objects from the 18th century. The absence of mirrors added by the Japanese, replaced instead by scenes of waterfalls, underscores the intriguing lack of cross-cultural communication during this period.

4. (Image from page 80, FIG. 53). Tabletop bureau surmounted by a dressing mirror frame, one of a pair, probably made in Guangzhou, China, and lacquered in Japan, c.1730–50, on a later stand, 174 x 80.5 x 50 cm © National Trust Images/Leah Band

Paraphernalia for preparing tea had been associated with China ever since the beverage had been introduced to Europe in the early seventeenth century. Tea was originally drunk as a medicine for headaches, fatigue, and digestion problems but later became an everyday drink for the wealthy. From the 1670s, stoneware teapots from Yixing in Jiangsu province were exported to Europe. Chinese pictorial wallpaper also became popular in the 1740s. The Little Parlour at Uppark was decorated with Chinese wallpaper and serving tea in this room was considered the ultimate display of femininity.

FICTIONS HAVE THEIR OWN LOGIC 1760-1780

In the face of William Chambers’ endeavours to “quell the extravagancies of chinoiserie” during the mid-eighteenth century, the overdoor shaped like a Chinese-style pavilion in the Chinese Room at Claydon House in Buckinghamshire by Luke Lighthouse as depicted in image 5. page 120, stands as “another unashamedly extravagant example of British orientalist design” (p. 121). De Bruijn says this portrayal is described as “completely divorced from the reality of China.”

5. (Image from page. 120, FIG. 85). Octagonal porcelain covered jar in a baluster shape, decorated in the famille rose palette, the lid with a lion finial, one of a pair, made in Jingdezhen, China, c.1735–45, 95.5 cm high, on wooden English-made stands © National Trust Images/Andreas von Einsiedel

In contrast to the exuberance evident in Lightfoot’s efforts, Thomas Chippendale’s approach appears notably genteel, as exemplified by the pier glass shown on page 133. It’s worth buying the book to see this one.

COMPETING PERSPECTIVES 1780-1870

Page 139 details how, towards the close of the 18th century and the inception of the 19th century, a shift occurred in European perspectives. Their own values and viewpoints came to the forefront, leading to a reversal where the history, society, governing structures, and artistic traditions of Japan and China were now perceived as “signs of inertia, backwardness, repetitiveness, and a mechanical mindset”.

As the First Opium War unfolded (1839-42) between Britain and China, Chinese wallpapers, retained their place of prominence in prestigious British homes. These once deemed ‘exotic’ products had seamlessly integrated into British material culture, thoroughly ‘domesticated’ and expected in elite interior decoration (p. 160). In contrast, European materials and techniques had become ingrained in Guangzhou during this period.

De Bruijn tells us that Owen Jones was one of a few architects and designers who wanted to “identify and expound on the ‘eternal principles’ of good design”. He also mentions how many ‘truly magnificent works of Ornamental Art’ from China to Britain at this time were caused by the destruction of public buildings during the Opium War (1856-60) and the British looting of the Yuanmingyuan Palace complex in Beijing (p.167).

THE AGE OF JAPONISME 1870 – 1900

De Bruijn starts this section by explaining from the early 17th century to the mid-19th century, exclusive trading privileges with Japan were confined to the Dutch and the Chinese, meticulously regulated by the Tokugawa shogunate, the country’s military leaders. In a pivotal turn of events in 1853, the US Navy, under the command of Commodore Matthew C. Perry, arrived off the coast of Edo (modern-day Tokyo). Employing warships, Perry exerted pressure on Japan to open its ports to international trade. This exertion led to the establishment of a new government headed by the Meiji Emperor in 1868. In response, Japan initiated an ambitious program of modernization and industrialization, strategically maximizing exports.

Europe experienced a surge in substantial quantities of Japanese fine and decorative art, a phenomenon that French collector Philippe Burty aptly termed ‘Japonisme’ in 1872. During this period, there was a perceptible shift as the demand for Chinese objects waned, and Japanese items were embraced as both ‘new’ and more authentically appealing.

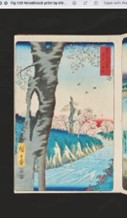

Famous woodblock prints like this one by Utagawa Hiroshige in image 6. page 171 were viewed “in the realm of tranquillity, beauty and art” (p. 170).

6. (Image from page 171, FIG. 120). Utagawa Hiroshige, Koganei, Musashi Province (Musashi Koganei), woodblock print, part of an album of prints entitled Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fuji sanjūrokkei), published by Tsutaya Kichizō, Edo (present-day Tokyo), Japan, 1858, 36 x 24 cm © National Trust Images/Leah Band

We learn that in 1862, Sir John Rutherford Alcock, the British Consul-General to Japan, presented a collection encompassing “prints, books, bronzes, porcelain, lacquer, and enamel” at the 1862 International Exhibition in London. This exhibition played a pivotal role in stimulating heightened demand for Japanese goods among the British public (p. 170).

In 1878, a law in Japan prohibited the public wearing of swords, yet the sustained interest from the West facilitated the continuation of swordcraft by artisans, catering to European and American interiors (p. 178). This extended not only to the skilled metalworkers but also to the reproduction of religious iconography, ensuring that motifs and symbols were preserved and not lost to posterity.

This Japanese cabinet from image 7. page 180 can be found at Hill Top, the Lake District home of children’s author Beatrix Potter. This style of cabinet using geometric patterning called Hakone wood mosaic was sold on the Tōkaidō highway between Edo and Miyako (modern-day Kyoto).

7. (Image from page 180, FIG. 128). Cabinet (soshoku tansu) decorated with wood mosaic (yosegi zaiku) and covered with clear lacquer, made in the Hakone area, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan, 1870–90, 83 x 89.5 x 47 cm © National Trust/Knole Conservation Studio

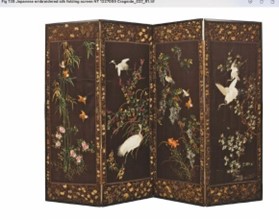

Starting from the 1870s, Japanese textile manufacturers embarked on creating exquisite products tailored to appeal to the European and American markets, particularly in the realm of ‘fine arts’. The tradition of pictorial embroidery, cultivated in Japan for centuries and reaching a pinnacle of sophistication during the Edo period (1615-1867), was a common practice found in various items like kimono, kimono sashes (obi), gift-wrapping cloths (fukusa), and textiles used in Buddhist temples. The remarkable level of expertise inherent in this art form is vividly demonstrated in a folding screen showcased in image 8. pages 196 and 197, likely crafted by the Chisō company in Kyoto.

8. (Image from pages 196 & 197, FIG. 139). Silk folding screen embroidered with birds and flowers against a black ground, possibly by the Chisō company, Kyoto, Japan, late nineteenth or early twentieth century, 170 x 244 cm © National Trust Images/Leah Band

NEW AND OLD ORIENTALISMS – The 20th century

According to de Bruijn, the British statesman George Curzon, during his tenure as Viceroy of India, amassed a significant collection of authentic Chinese artifacts. Subsequently, he generously donated many of these pieces to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Perceiving himself as a British imperial overlord, Curzon likely believed it was his prerogative to acquire and preserve art, including items looted from Chinese palaces, by placing them in museums.

De Bruijn tells us the late nineteenth or early twentieth-century screen showcased at Greenway in Devon, which is featured on the book cover and page 209, epitomizes Chinese ‘imperial’ taste, despite likely being a new creation. In China, such screens, known as pingfeng, served the dual purpose of wind shields while functioning as movable art. Crafted with meticulous detail, they incorporated blue and purple kingfisher feathers, ivory, coral metalwork, and a textile background.

The screen at Cragside in Northumberland, featured in image 9. page 210, serves as the Japanese counterpart to the pingfeng depicted on page 209 and the cover. Painted by Takeuchi Seihō in the Nihonga style (Japanese painting), distinct from the yōga (Western painting) style rapidly emerging in the late nineteenth century, this piece likely functioned as a gift from a high-ranking Japanese visitor during the late Victorian and Edwardian periods. De Bruijn tells us Seihō was sponsored by the Japanese government to study Western art in Europe. Seihō imbues this screen with a romantically Turneresque style, while the depiction of the deer symbolizes the essence of autumn.

9. (Image from page 210, FIG. 148). Single-panel screen (tsuitate) in red lacquer inset with a watercolour depicting a pair of deer lying in a meadow by Takeuchi Seihō, probably first quarter of the twentieth century, 37 cm high © National Trust Images/Leah Band

Persistently, there exists a “tenacity of orientalist self-referentiality, always preferring fiction over fact” (p. 237). A notable example of this phenomenon is evident in the gramophone showcased in image 10. page 231 within Lady Bearsted’s bedroom at Upton House in Warwickshire. Accompanied by Japanese prints, an imitation-lacquer bed, and a ‘pagoda’ shaped overmantel mirror, this gramophone, encased in an early 18th-century imitation lacquer cabinet, exemplifies how this trend of orientalizing also encompassed new technology (p. 232).

10. (Image from page 231, FIG. 163). Gramophone decorated in imitation red and gold lacquer, 1920s–30s, 59 x 96 x 64 cm © National Trust Images/Nadia Mackenzie

On the final pages, Bruijn summarises the book with this paragraph: “British engagement with China and Japan from about 1600 onwards triggered desire, admiration, inspiration, and imitation; it was also accompanied by appropriation, misunderstanding, dismemberment, and caricaturing.” (p. 240) British and other European commentators took on the role of presumed experts on China and Japan, positioning themselves as self-appointed gatekeepers. In this capacity, they expanded the body of knowledge while concurrently distorting it with their own priorities and preconceptions (p. 240).

Thank you for delving into one of my most extensive yet gratifying reviews to date. This book is truly enthralling, and adorned with magnificent images. It’s a valuable investment and a delightful addition to any coffee table, ideal for sharing with others.

‘Borrowed Landscapes: China and Japan in the Historic Homes and Gardens of Britain and Ireland‘ by Emile de Bruijn. ISBN-13: 978-1781300985, (256 pages), Philip Wilson Publishers (12 Oct. 2023), hardback £35.00.

…………………………………………………….

If you’re interested in the fusion of art and fashion within the context of China, I highly recommend “The First Monday in May” on Netflix. Starring Dame Anna Wintour, editor-in-chief of Vogue since 1988, the documentary delves into the creation of the record-breaking 2015 art exhibition “China: Through the Looking Glass” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, curated by Andrew Bolton. This particular Costume Institute Benefit aimed to challenge the orientalist stereotypes associated with China and explore the authentic mutual exchange between China and the Western world through fashion and film.